PREMIERE PRO FOR PROS

If you’re in this class, you probably have some experience with Adobe Premiere Pro. If not, you should be familiar with another editing system, such as Final Cut Pro or Avid. In other words, you should already have an understanding of the basic mechanics of editing: importing and reviewing media, trimming and rearranging clips on a timeline, adding music and adjusting levels, etc. If you need a refresher on the basics, I’d suggest checking out this document, which I use to teach Premiere to beginners.

Part of the purpose of this class is to learn the “best practices” for using Premiere in a professional environment. That means taking some extra steps in terms of organization, file management, and project set-up.

Get Organized

The first thing that you need to understand about Premiere is the way that the program handles media. You can use all different kinds of files in Premiere – video of various formats, still images, music and audio clips, etc. – by importing them into the project window. However, when you import a file into Premiere, that file doesn’t actually move; Premiere simply remembers where it is. So, if you have a file on your desktop and import it into a Premiere project, then close the program and move the file, Premiere won’t be able to find that file the next time you open the project.

For this reason, I always recommend creating a “project folder” whenever you start a new project in Premiere. You should put everything that you’ll be using for your project into that folder. That might mean a lot of copying and pasting, but it’s worth it – by keeping everything together, you can easily move your project from one computer to another, or create a backup. Within your project folder, it’s almost always worth doing some more organization. You should probably create a folder for video files, a folder for music, a folder for sound effects, and so on. Remember to do all this copying and organization before you import your media into Premiere itself.

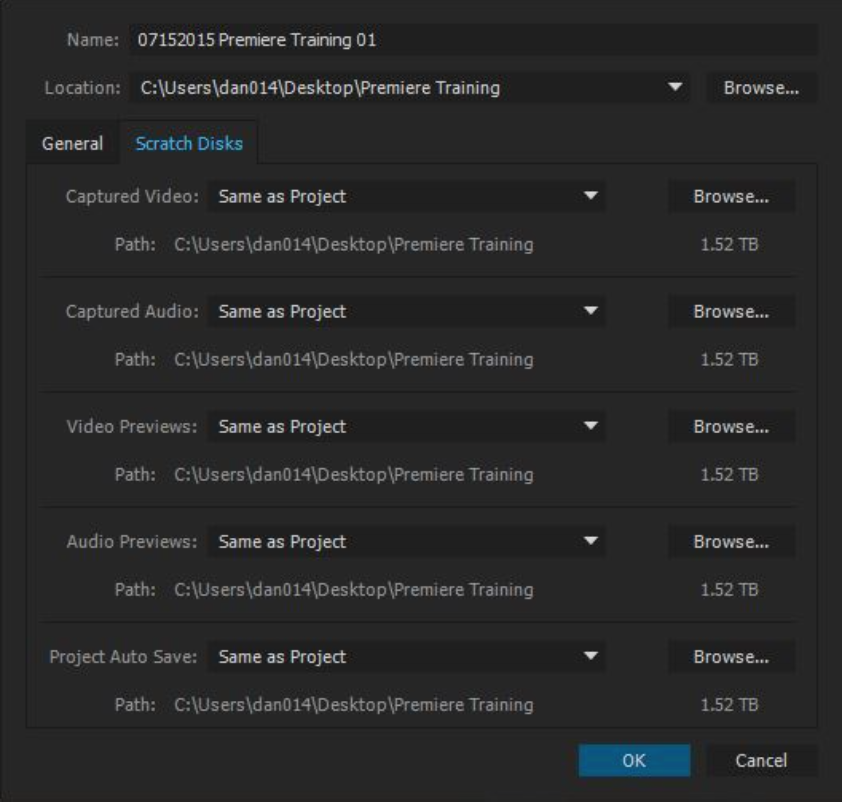

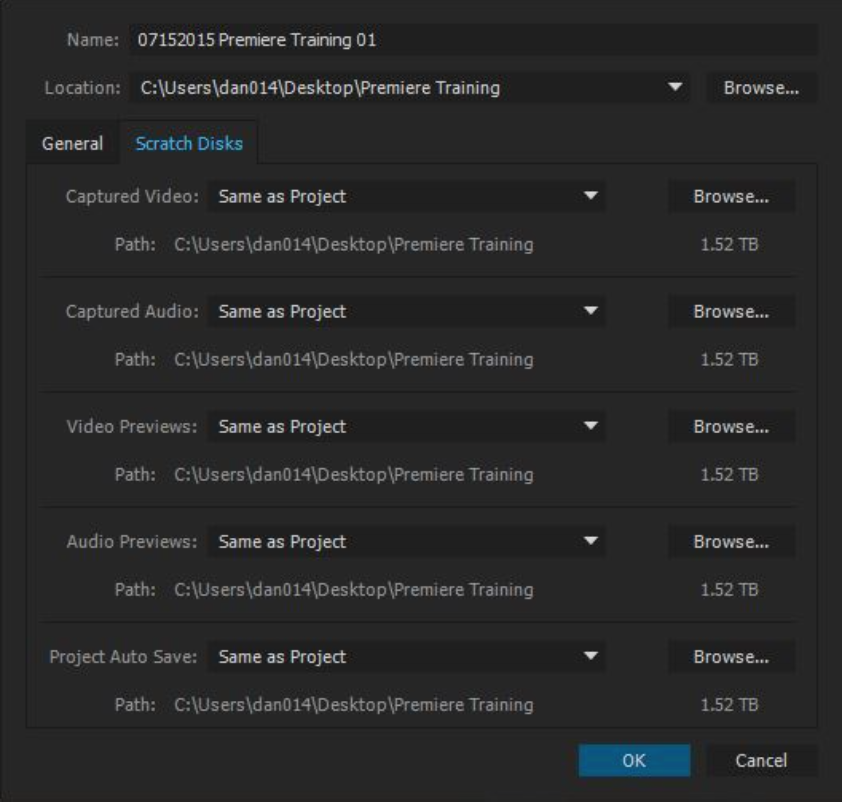

When you do open up Premiere, you’ll want to create a new project. Be sure to give it a descriptive name – I like to incorporate the title, approximate date, and version number (for example, “Bucknell Convocation 11-2016 v01”). Set the location to your project folder – the same place you’ve been putting your folders of media. Finally, click over to “Scratch Disks” and make sure that they are all set to “Same as Project.” This will ensure that Premiere stores all of its files in the same place.

Once you have your files in Premiere, it’s a good idea to do some further organization via renaming and bin creation. I do not recommend renaming files before you import them, because that can make it difficult to relink them if you need to go back to the originals. Instead, I’d suggest renaming your files within Premiere, which only affects how the file’s name appears within the program – it does not change the name of the file in your project folder. To rename something, either use a slow double-click, or right-click and choose “rename.”

With your files renamed, you can begin to sort things into bins, which behave just like folders – you can create a new bin by clicking the little “folder” icon at the bottom of the project window. At the very least, you should have bins for your footage, music, stills, and other categories of media. If you’re working on a more involved project with lots of media, you will probably want to create bins within bins – for example, bins for different locations or shoot days within your footage bin. It can also be useful to color code your media, which you can do by right-clicking and choosing “label.”

Depending on the footage you’re working with, one last organizational step you may want to tackle is the creation of subclips. Subclips are useful when you have a long clip that you want to use multiple pieces of. If you double-click on a piece of video footage, it will open in the Preview Window. This is where you review your footage before dragging it to the timeline and beginning to edit. In the Preview Window, you can use the “I” and “O” keys to set in and out-points around sections of the footage. You can then right-click and choose “Create Subclip.” Subclips appear with the rest of your media and look like new pieces of footage. They exist only within Premiere – again, the original files are not being duplicated, moved, or modified.

Before you can do any editing with your newly-organized media, you need to create a sequence in the Timeline. The easiest way to do this is by right clicking on a video clip in the media window and selecting “New sequence from clip.” This will create a sequence with the same resolution and frame rate settings as the clip – so a 1920 x 1080 video with a frame rate of 24 frames per second will create a sequence with those settings. You can use multiple resolutions and frame rates in the same sequence, but you should create the sequence using a clip with the settings you want for your final project. You should also rename your sequence, since it will automatically reuse the same name as whatever clip you created it from.

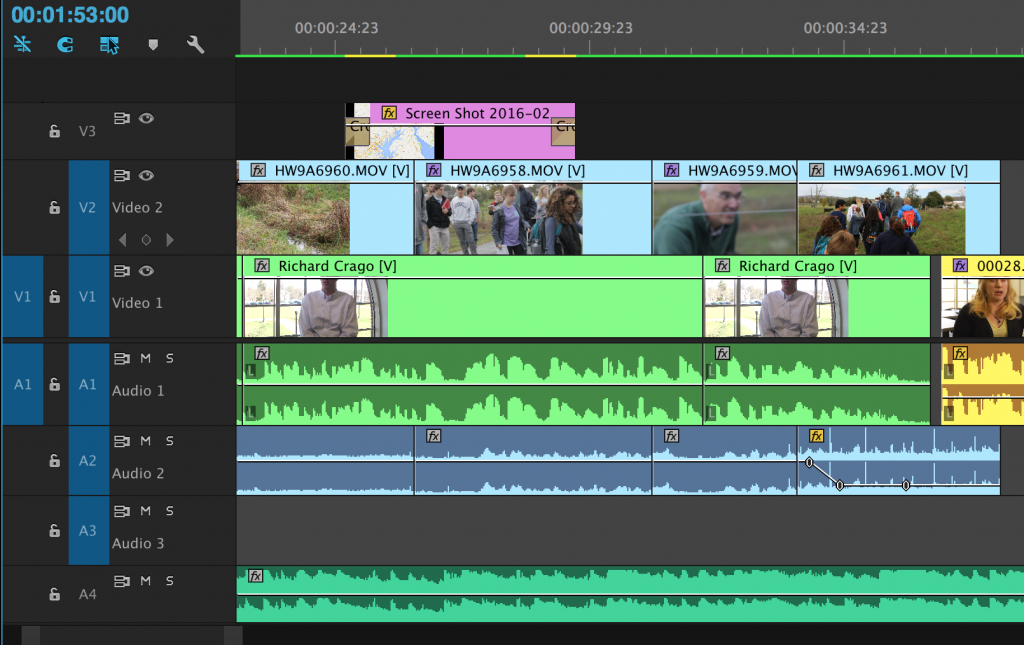

When you’re ready to start editing, you should carry your organization over into the Timeline sequences as well. The timeline is made up of layers, or “tracks,” and you can create as many as you want by right clicking and choosing “Add Tracks.” It’s generally a good idea to put different types of media on different tracks – for example, if you were editing a video of interview footage with some stills used as cut-aways, you should put the interview footage on one layer and all the stills on another. On the audio side, I like to have a track for in-camera audio, a track for externally-recorded audio, a track for sound effects, a track for music, a track for room tone, and so on. Because video tracks can be hidden (by clicking the “eye” icon) and audio tracks can be muted or soloed (by clicking “M” or “S”), organizing your media by tracks allows you to check the different parts of your project quickly and easily.

Basic Editing

Now that we’ve spent some time getting familiar with the Premiere workspace, we’re ready to move on to actually editing a project. If you already have some editing experience, you shouldn’t have a hard time adapting to working in Premiere. If this process is new to you, the best thing to do is to just mess around with the program. The good news is that all video editing programs operate in generally the same way – so if you learn one, you can probably figure the rest out. They all have their own quirks, but the process of actually editing video footage is pretty much the same.

The simplest way to edit is by grabbing the clips in the Timeline and moving them around. If you grab the beginning or end of a clip, you can shorten or lengthen it. Using the razor blade tool (keyboard shortcut C) will split a clip. If you drag one piece of footage onto another, the new footage will “overwrite” the old footage (which will disappear from the sequence). This is called an overwrite edit. If you drag one piece of footage onto another with the command key held, all the footage after the edit point will slide down and the new footage will be inserted there. This is called an insert edit.

These relatively simple actions are the basic building blocks of all video editing. Everything else is secondary, so be sure to get comfortable moving media around in this way.

Every editor has a slightly different style of working. I like to start with large chunks of footage in my timeline, then rearrange and block out the piece as a whole. When everything is in roughly the place I think it belongs, I make successive passes through the footage, refining and tightening things up as I go. On each pass, I try to be increasingly critical about what stays in the edit. After several iterative edits of the raw footage, I add transitions and keyframed effects. Fine audio adjustments and color correction are usually the last steps.

Transitions and Effects

Premiere has a variety of different video and audio transitions built-in – wipes, iris simulations, 3D effects, morphs, and more. Occasionally, for a very specific kind of project, these are helpful. Generally, though, they’re garishly cheesy and most of them should be avoided. When you do use a transition, you probably want to do so in a way that doesn’t call attention to the transition itself; it should enhance the footage, not distract from it. Use them sparingly. Your best bets are the simple ones – either a cross-dissolve or a dip-to-black. Even these can be visually tiring if overused, however.

You can add a transition by dragging it from the appropriate drop-down in the Effects menu. A transition can be placed either at the end of one piece of footage or between two (provided there is no gap). You can right-click at the end of a piece of footage and choose “Apply default transition.” This will add a simple cross-dissolve to both video and audio. This can also be done by highlighting footage and using the Command-D shortcut. You can adjust the parameters (length, etc.) of any transition by clicking on it and using the Effect Controls window.

Effect Controls is also where you adjust the various properties and effects of the media in your sequence. If you click on a piece of video, it will show up in the Effect Controls. You should see a section called “Motion” near the top — this is where you can change the scale, position, anchor point, and rotation. The opacity controls are there as well. You can use these settings to adjust the framing of a shot, or for more creative effects such as split-screen and overlays. Any other effects that you add to your footage will appear below the default adjustments. Effects are applied in the order they appear, which can change the overall look of the footage. For example, if you apply a color correction and a glow, switching their order will alter the final result. Effects can be reordered, as well as copied and pasted (although only one at a time). Under the Audio section are controls for volume and pan. We’ll go more in-depth with audio effects next week.

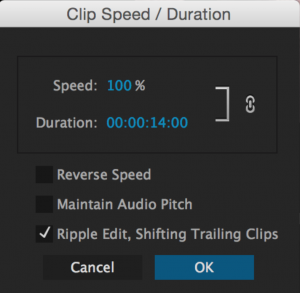

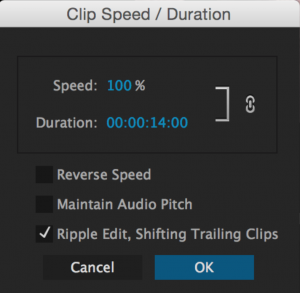

To change the speed of a clip, right-click on it in the Timeline and choose Speed/Duration from the drop down menu. Adjusting the speed to over 100% will make the clip speed up; adjusting the speed to less than 100% will make it slow down. You can also reverse the clip using Reverse Speed tick box. Be aware that your footage will start to look choppy if you slow it down significantly. One important option in the Speed/Duration window is the Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips tick box. Checking this box will move all proceeding clips in the sequence relative to the new duration of the clip you adjust. So, if you change the speed on a 5 second clip to 50%, that clip will become 10 seconds long. If you check Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips, no existing clips will be overwritten – instead, they will just move down the timeline.

To change the speed of a clip, right-click on it in the Timeline and choose Speed/Duration from the drop down menu. Adjusting the speed to over 100% will make the clip speed up; adjusting the speed to less than 100% will make it slow down. You can also reverse the clip using Reverse Speed tick box. Be aware that your footage will start to look choppy if you slow it down significantly. One important option in the Speed/Duration window is the Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips tick box. Checking this box will move all proceeding clips in the sequence relative to the new duration of the clip you adjust. So, if you change the speed on a 5 second clip to 50%, that clip will become 10 seconds long. If you check Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips, no existing clips will be overwritten – instead, they will just move down the timeline.

Exporting

When your draft is finally finished, you’ll need to export it. The first thing you should do is set an In and an Out Point around your project. If you don’t do this, Premiere will export everything in the current sequence. You bring up the render options by choosing File>Export>Media… from the menu bar, or by simply pressing Command-M. There are a ton of render format options and if you know what you’re doing, you can really define all the parameters of your finished video file. Premiere also gives you lots of useful presets, though. For video that will go on the web, the H.264 format does a great job. If you plan on uploading your video to a streaming site, such as YouTube or Vimeo, you can select one of those options from the Preset drop-down menu. The YouTube and Vimeo presets generally do a nice job of keeping the file size manageable and the quality of the video high.

Before you export your project, you should click on the Output Name to input what the file will be called and where it will go. It may be a good idea to create a sub-folder within your master folder just for rendered video. Most of the other options in this window can be left alone, at least for now. You have two options for rendering the video – if you click Queue, you will bring up the Media Encoder program and it will load your project. This is fine, but it’s a bit more complicated than is strictly necessary. If you click Export, the video will begin to render within Premiere. When it’s finished, be sure to watch it in its entirety to make sure that there weren’t any errors in the exporting process — it does happen, from time to time.

Project 2: Start Cutting

The best way to really learn a program like Premiere is to just start using it. Download the media at this link, then set up an organized project folder and Premiere file. In the folder, organize the media by type – stills, footage, sound effects, and music. Import all the media into Premiere and organize it there as well – create bins and rename the files so that they make sense at a glance. With everything set up properly, create a timeline sequence and make a simple video project. It doesn’t have to be brilliant – or even coherent – I just want you to familiarize yourself with the tools, interface, and process of editing in Premiere. Make something between 30 seconds and a minute long, then export it using the 1080HD Vimeo preset in the H.264 format.

With that done, take your project folder with everything in it (media, Premiere file, exported project, etc.), compress it (on a Mac, right click on the folder and select “Compress”), and upload the resulting zipped file to your Google Drive. You should then be able to send me a download link to that file. If you’ve organized everything properly, I should be able to unzip the file and open your project on any computer running Premiere. This assignment is as much about media organization as it is about editing, so I want to see your project folder and Premiere file in addition to your finished piece.

I realize that this is a lot to take in, especially if Premiere is new to you. If you find yourself stuck, feel free to contact me – I can either help you troubleshoot over email or set up a meeting to go over things in person. Be sure to send your finished assignment to me by the morning of Thursday, September 8, so that I can look over everything and get stuff posted before class that day. Have fun!

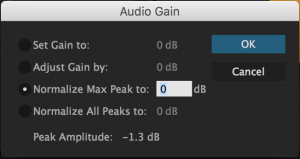

If you have an audio clip that was recorded too low or too high, you can also make an automated adjustment called “normalizing.” Right-click on a clip and select “Audio Gain…” – this will bring up a small menu with a few different options. You can either normalize the “max peak” or “all peaks” – the two work in similar ways, so you probably won’t see a huge difference between the two. Keep in mind that since this is an automated effect, you’ll want to pay close attention to how it changes your clip. You can also set or adjust the gain of a clip in this menu, if the volume controls in the Effect Controls window are insufficient.

If you have an audio clip that was recorded too low or too high, you can also make an automated adjustment called “normalizing.” Right-click on a clip and select “Audio Gain…” – this will bring up a small menu with a few different options. You can either normalize the “max peak” or “all peaks” – the two work in similar ways, so you probably won’t see a huge difference between the two. Keep in mind that since this is an automated effect, you’ll want to pay close attention to how it changes your clip. You can also set or adjust the gain of a clip in this menu, if the volume controls in the Effect Controls window are insufficient.

To change the speed of a clip, right-click on it in the Timeline and choose Speed/Duration from the drop down menu. Adjusting the speed to over 100% will make the clip speed up; adjusting the speed to less than 100% will make it slow down. You can also reverse the clip using Reverse Speed tick box. Be aware that your footage will start to look choppy if you slow it down significantly. One important option in the Speed/Duration window is the Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips tick box. Checking this box will move all proceeding clips in the sequence relative to the new duration of the clip you adjust. So, if you change the speed on a 5 second clip to 50%, that clip will become 10 seconds long. If you check Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips, no existing clips will be overwritten – instead, they will just move down the timeline.

To change the speed of a clip, right-click on it in the Timeline and choose Speed/Duration from the drop down menu. Adjusting the speed to over 100% will make the clip speed up; adjusting the speed to less than 100% will make it slow down. You can also reverse the clip using Reverse Speed tick box. Be aware that your footage will start to look choppy if you slow it down significantly. One important option in the Speed/Duration window is the Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips tick box. Checking this box will move all proceeding clips in the sequence relative to the new duration of the clip you adjust. So, if you change the speed on a 5 second clip to 50%, that clip will become 10 seconds long. If you check Ripple Edit, Shift Trailing Clips, no existing clips will be overwritten – instead, they will just move down the timeline.